hen I met people, back when I was a teacher, they would often ask what I did for a living. When I said that I was a teacher, they would often ask the next logical question: what did I teach? "English," I'd say, and the answer regularly came back, "Oh! I was terrible in English! My grammar is awful!" (embarrassed laugh). When I hastened to add that I taught very little grammar, I usually could't refrain from adding, "I teach literature--medieval literature." (pause) "You know, Chaucer." A look often crossed my new acquaintance's face that told me that I might have done better if I had said I was a geek, or perhaps a chicken sexer. Occasionally I found myself gazing into the Face of Pity. hen I met people, back when I was a teacher, they would often ask what I did for a living. When I said that I was a teacher, they would often ask the next logical question: what did I teach? "English," I'd say, and the answer regularly came back, "Oh! I was terrible in English! My grammar is awful!" (embarrassed laugh). When I hastened to add that I taught very little grammar, I usually could't refrain from adding, "I teach literature--medieval literature." (pause) "You know, Chaucer." A look often crossed my new acquaintance's face that told me that I might have done better if I had said I was a geek, or perhaps a chicken sexer. Occasionally I found myself gazing into the Face of Pity.

Such people were (and are) not always

grocery store clerks or engineers; often they were my university

colleagues. For that reason, I prepared a little tour through my world,

in an effort to show visitors why I fell in love with this far-off time,

a time when people spoke and wrote in a strange and (for us) difficult

form of English, did without e-mail, and (if they were upper class)

pretended that women were all-powerful, even though it was more a man's

world than we shall ever see.

So come along. I'll point out a few

things along the way. If they don't interest you, keep walking. If they

do, stop and investigate (you can click on many of the pictures to see

larger versions), and you'll see what is so splendid and strange and

wonderful about my Middle Ages.

My own first encounter with the

Middle Ages was with the works of Chaucer (which I won't subject you to).

His pilgrims, a motley crew riding on horseback from the London suburbs

to the shrine of St. Thomas Becket in Canterbury (Kent), are an

interesting bunch of people, who interact much as we do. They jockey for

position, show off, pick fights, get tipsy, and act so much like people I know that

my first encounter was a very pleasant kind of shock. I knew them--the

Middle Ages suddenly felt very close.

then

discovered that the world they inhabited had left all sorts of remains,

remains that could be seen in books if not in person--and who knew but then

discovered that the world they inhabited had left all sorts of remains,

remains that could be seen in books if not in person--and who knew but

that I might

some day be able to stand in front of a case in the British

Museum and see the Anglo-Saxon treasure that was pictured in books,

or even turn the pages of a manuscript? Age, the distant past, its simultaneous

distance and accessibility fascinated me. To touch something that a

fourteenth-century Englishman had touched, owned, valued seemed an intriguing

and tantalizing possibility. I could see a little holy water flask,

made of lead, that a pilgrim to Canterbury to visit the tomb of St.

Thomas a Beckett had bought and later lost along the banks of the Thames.

Despite the damage it had sustained in the intervening 600 years, I

could see that it was an inexpensive, yet precious souvenir (though,

in calling it a "souvenir," I knew I was speaking from another

culture).

that I might

some day be able to stand in front of a case in the British

Museum and see the Anglo-Saxon treasure that was pictured in books,

or even turn the pages of a manuscript? Age, the distant past, its simultaneous

distance and accessibility fascinated me. To touch something that a

fourteenth-century Englishman had touched, owned, valued seemed an intriguing

and tantalizing possibility. I could see a little holy water flask,

made of lead, that a pilgrim to Canterbury to visit the tomb of St.

Thomas a Beckett had bought and later lost along the banks of the Thames.

Despite the damage it had sustained in the intervening 600 years, I

could see that it was an inexpensive, yet precious souvenir (though,

in calling it a "souvenir," I knew I was speaking from another

culture).

t

the t

the  other end of the spectrum, I discovered the glory of early Irish

manuscripts, like so many other people, through the Book of Kells, written

in the late eighth century. The so-called "carpet pages,"

so ornately decorated that they look like oriental carpets, and the

magnificent opening pages, like this one to the Gospel of St. Luke,

appealed to me first. Later, simpler pages, just as intriguing in their

details, like this one of Matthew 24:19-24, drew me back to these testaments

to Irish high culture and religious devotion.

other end of the spectrum, I discovered the glory of early Irish

manuscripts, like so many other people, through the Book of Kells, written

in the late eighth century. The so-called "carpet pages,"

so ornately decorated that they look like oriental carpets, and the

magnificent opening pages, like this one to the Gospel of St. Luke,

appealed to me first. Later, simpler pages, just as intriguing in their

details, like this one of Matthew 24:19-24, drew me back to these testaments

to Irish high culture and religious devotion.

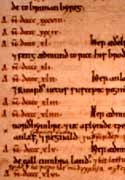

ven ven

the

Anglo-Saxons, who kept up a "national" chronicle until William

the Conqueror invaded England in 1066 (and beyond), had left precious

remains. A man wrote about the troubles and successes of his own time on

these very parchment leaves. I could look at them, even touch them, and

then turn to a scholarly edition to read them and read about them.

Afterward, I could go and look again and understand better and better

what I was looking the

Anglo-Saxons, who kept up a "national" chronicle until William

the Conqueror invaded England in 1066 (and beyond), had left precious

remains. A man wrote about the troubles and successes of his own time on

these very parchment leaves. I could look at them, even touch them, and

then turn to a scholarly edition to read them and read about them.

Afterward, I could go and look again and understand better and better

what I was looking

at,

picturing more and more clearly where and when and why and by whom it was

written. It seemed (and seems) important. at,

picturing more and more clearly where and when and why and by whom it was

written. It seemed (and seems) important.

I also came to appreciate how precious

the bits of early medieval literature I'd read were. Nearly all of my

students like Beowulf, a poem written before the year 1000. It

survives into modern times in only one manuscript (above). That manuscript was

in a library that had a great fire in the seventeenth century. As you

can see from this parchment leaf, the top and one side were badly scorched

and crumbled away. If it had been shelved in a different bookcase, it

would be gone.

n Ireland n Ireland

people living in about the same

age left behind monumental stone crosses that still stand in churchyards

and inside churches, like this huge one at Monasterboice, outside

Dublin. The carving, which covers all the surfaces of the cross,

presents the Crucifixion at the center. Everything around it serves to

explain and enrich our understanding of that scene of a god dying. These

people were rock-solid in their faith, and that, too, made me want to

understand them better. How strange such an idea is in our world. people living in about the same

age left behind monumental stone crosses that still stand in churchyards

and inside churches, like this huge one at Monasterboice, outside

Dublin. The carving, which covers all the surfaces of the cross,

presents the Crucifixion at the center. Everything around it serves to

explain and enrich our understanding of that scene of a god dying. These

people were rock-solid in their faith, and that, too, made me want to

understand them better. How strange such an idea is in our world.

|

![]()

![]()